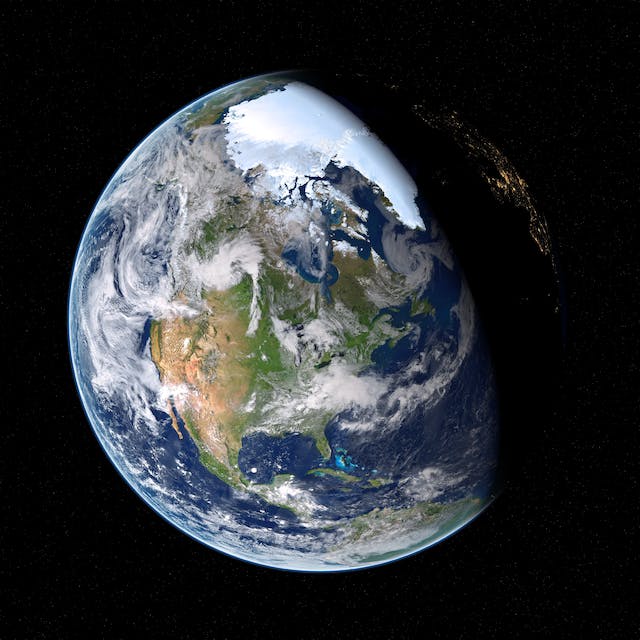

Globalization — a process which gives, according to the dictionary definition, various activities and aspirations an “extension which concerns the whole world” — began a long time ago. Thousands of years before the root word appeared — “world” or “globe” — our ancestors had already spread across the face of the earth. In fact, their migrations and settlement of all continents (apart from Antarctica) represented a kind of proto-globalization. About fifty thousand years ago, homo sapiens, which appeared in East Africa, began to migrate to the four corners of the world, including North and South America. Rising sea levels at the end of the Ice Age had separated the American continent from the Eurasian mass, creating two worlds that were now cut off from each other. They would not reunite were now cut off from each other. They would not meet again until 1492 when Christopher Columbus landed by happy coincidence on the West Indian islands. That same year, a German geographer, Martin Behaim, would construct the first known terrestrial globe.

Globalization — a process which gives, according to the dictionary definition, various activities and aspirations an “extension which concerns the whole world” — began a long time ago. Thousands of years before the root word appeared — “world” or “globe” — our ancestors had already spread across the face of the earth. In fact, their migrations and settlement of all continents (apart from Antarctica) represented a kind of proto-globalization. About fifty thousand years ago, homo sapiens, which appeared in East Africa, began to migrate to the four corners of the world, including North and South America. Rising sea levels at the end of the Ice Age had separated the American continent from the Eurasian mass, creating two worlds that were now cut off from each other. They would not reunite were now cut off from each other. They would not meet again until 1492 when Christopher Columbus landed by happy coincidence on the West Indian islands. That same year, a German geographer, Martin Behaim, would construct the first known terrestrial globe.

This re-establishment of links between continents, born from the trade routes opened by Columbus, is one of the significant events in the history of globalization. The discovery of the New World would bring together peoples who had remained separated for more than ten thousand years. No less important was the movement of plants and animals. For example, a Peruvian tuber, the potato, has since become a staple food around the world; the red pepper from Mexico would conquer all of Asia, and an Ethiopian crop, the coffee tree, would take root from Brazil to Vietnam. During this time, societies not only evolved in opposite directions and established various economic and political structures but also invented different techniques, planted different crops, and, above all, gave birth to different languages and ways of thinking. It is this plurality that has given the resumption of links between civilizations its value and its scope.